Listen

Track:

About

Music-making was always a part of Samuel Barber’s life, from his earliest years. The nephew of contralto Louise Homer and her husband, the prolific song writer Sidney Homer, Barber had announced his vocation in a note written to his mother at the age of nine:

“I was meant to be a composer and will be I’m sure…Don’t ask me to try to forget this unpleasant thing and go play football–please.”

Samuel Osborne Barber II was born March 9, 1910, in West Chester, Pennsylvania, the son of a prominent doctor. Young Sam studied piano at six, began composing at seven, served as a church organist while still in his teens, and developed his attractive baritone voice to the point where he entertained the thought of becoming a professional singer. Enrolled in the newly-founded Curtis Institute of Music at fourteen, Barber studied piano with Isabelle Vengerova, composition with Rosario Scalero, singing with Emilio de Gogorza, and conducting with Fritz Reiner, and formed a life-long friendship with Gian Carlo Menotti, whom he met in 1928 in Philadelphia. Two years of training in Italy after winning the 1935 Prix de Rome and numerous European jaunts helped the emerging composer to shake off the conservative influences of Homer and Scalero and shape his own distinctive musical language.

Barber composed a wide range of stage, orchestral, chamber, piano, choral, and vocal works in what he unassumingly insisted was a personal style “born of what I feel..I am not a self-conscious composer.” His discipline and use of traditional forms earned him the reputation of a classicist. Virgil Thomson once wrote that Barber was laying to rest the ghost of Romanticism without violence, though in light of the composer’s lush lyricism, deft dramatic sense, and inclination toward Romantic poetic sources (especially in his vocal writing), this comment ultimately proved to be off-mark. Throughout his catalogue of works, Barber adhered stubbornly to his own inner voice–a voice rich in subtlety and sumptuousness that relied deeply on melody, polyphony, and complex musical textures, all fused with an unerring instinct for graceful proportion and an unabashed affinity for Romantic thought and emotion.

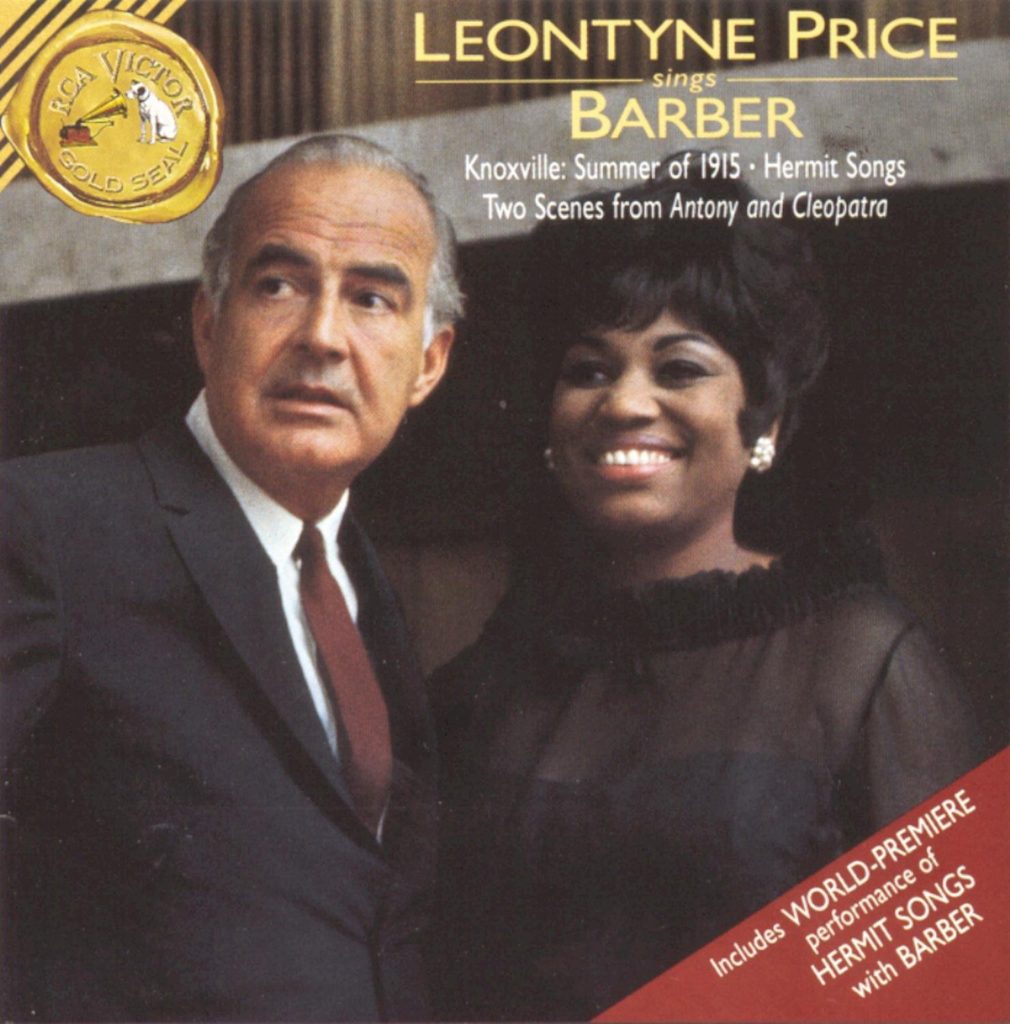

His symphonic catalogue abounds in exquisitely crafted, yet deeply emotive, works, among them the lyrical 1933 Music for a Scene from Shelley, Symphony No. 1 (1936), the Adagio for Strings (1938), and his Cello Concerto, op. 22 (1945), to name but a few. His works for the stage include the Martha Graham ballet Medea, the chamber opera A Hand of Bridge, and his two full scale operas, Vanessa (1958) and Antony and Cleopatra (1966). Despite the fact that the Shakespeare work, which opened the new Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, was subjected to critical scorn, its failure was due less to Barber and far more to the overblown technical disaster created by stage designer Franco Zeffirelli. Though a revised version presented by the Juilliard School in 1975 and a subsequent production by the Chicago Lyric Opera have gone a long way in reappraising Barber’s score, the composer himself, devastated by the initial response, never fully recovered from the depression that followed. In addition to his symphonic compositions, Barber showed a particular flair in writing for both the piano and the voice. From the Brahmsian lyricism of his Interlude No.1, composed in his Curtis days and premiered only fifty years later by John Browning, to the virtuosic, passionate, and compelling Piano Sonata, op. 26, to the Pulitzer Prize-winning Piano Concerto, op. 38, Barber has made landmark contributions to the keyboard repertoire.

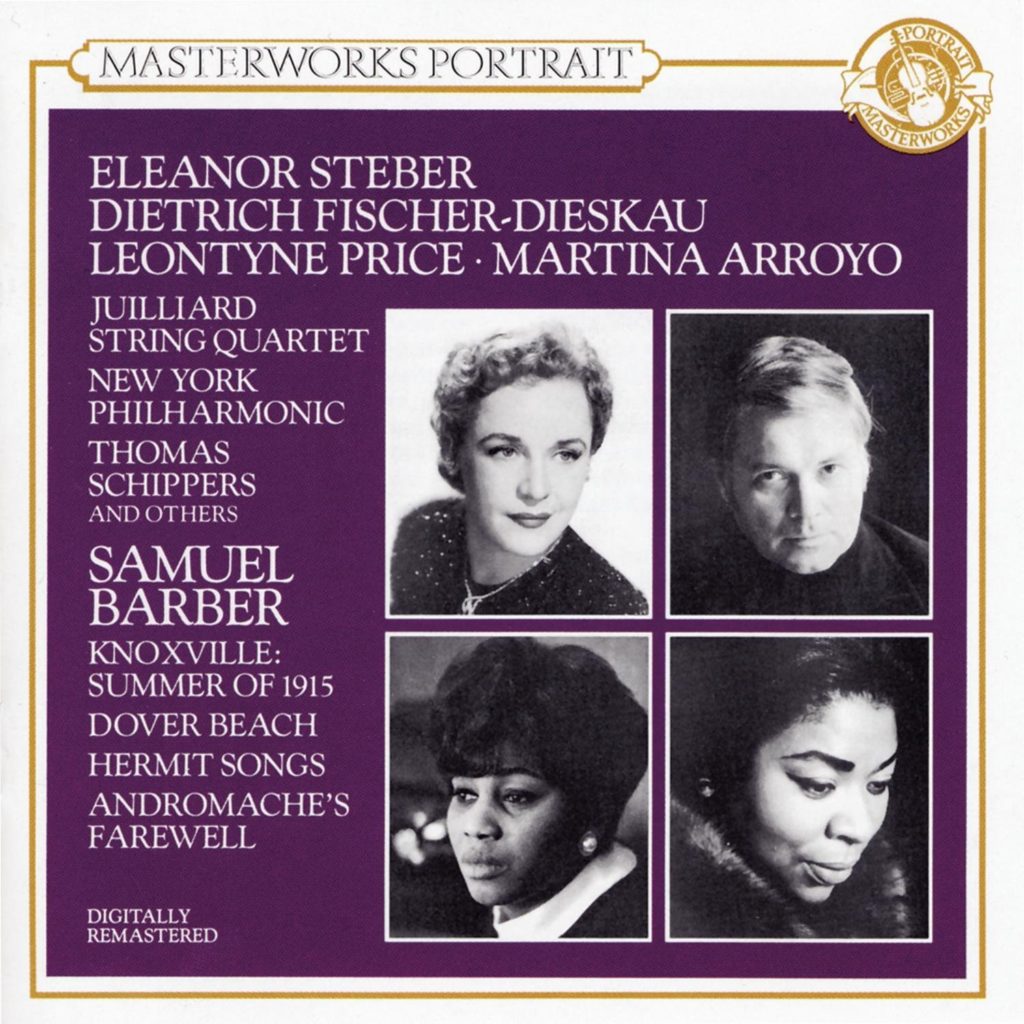

But perhaps it is as a songwriter that Barber is at his most Romantic and impassioned. A fine baritone himself, Barber’s love of poetry and his intimate knowledge and appreciation of the human voice inspired all his vocal writing. John Browning asserts that throughout Barber’s life, the composer was never without a volume or two of poetry at his bedside. Poetry was, Browning believes, as necessary to his existence as oxygen. In his impeccable choice of song texts, Barber was drawn to a wide variety of contemporary writers, prominent among them the Georgian School, the Irish bards, and the French Symbolists, who were, in fact, intimately connected with the linguistic experiments of the 20th century Irish master James Joyce, as well as to contemporary American voices like James Agee. The complete edition of the songs recorded for Deutsche Grammophon by Thomas Hampson, Cheryl Studer, John Browning, and the Emerson String Quartet in 1992 not only revealed the range of Barber’s vocal inspiration, but it offered ten previously unpublished (and subsequently issued) songs. These piano-vocal compositions, when taken together with Barber’s two song settings for orchestra (Knoxville, Summer of 1915 to words by James Agee and Dover Beach to a Victorian text by Matthew Arnold), make a powerful case for Barber as one of the twentieth century’s most accomplished songwriters.

While he sometimes dismissed his youthful works, Barber retained a special fondness for Dover Beach (1931)–perhaps because he had performed it often himself, and had recorded it in 1935, but more likely because he found in it and in Arnold’s poem of pessimism and stoic despair a renewed meaning. Almost fifty years later, when the composer was seventy, he remarked on the maturity of his inspiration in Dover Beach and the timelessness of Arnold’s text, saying that the emotions seemed contemporary.

Surely Barber was not only speaking of the universal resonance of the work, but of its personal one as well. For the man whose intensely private, reserved, urbane, and erudite exterior masked deep wellsprings of passion; for the artist whose expansiveness of feeling was always tempered by the mésure of form; for the composer whose insistence that melody and tonality fuse with modern dissonant harmonics, the artistic journey was a daunting and sometimes even depressing one.

Especially in his last decade after the initial failure of Antony and Cleopatra, Barber had reason to feel his works neglected and his mission misunderstood.

Composing became increasingly difficult for him, though he battled on, producing a trickle of important works, among them a piano Ballade; The Lovers, for baritone, chorus, and orchestra; the Third Essay for Orchestra; and the late songs from Opus 41 and Opus 45. He also continued to confront his creative destiny with the same outward stoicism so poignantly reflected in Arnold’s poem. That he never lived, as John Browning laments, to see the current revival of tonalism and lyricism among those young composers who, having found serialism a cul-de-sac, now regard Barber as their prophet is, of course, a great tragedy. And yet, each year, as Barber’s compositions find new audiences and his reputation as one of the most important 20th century composers continues to grow, one may be permitted to imagine that Arnold’s tremulous cadence of sadness, with its impassioned counter-plea “Ah love let us be true/To one another!” has found an enduring answer in Samuel Barber’s stubborn, loving, faithful enduring commitment to a Muse and to a vision that were painfully, but inspiringly, prescient.

–Thomas Hampson and Carla Maria Verdino-Süllwold, PBS I Hear America Singing

During the mid-twentieth century, Samuel Osborne Barber II was one of the most frequently performed composers in the United States and Europe. He was known for his trademark lyrical style, and he never abandoned that expressive voice. Unlike many of his fellow composers, who performed or taught to make a living, Barber was able to dedicate nearly all his time to composition. He was also fortunate in having virtuoso performers premiere almost all of his music. With over 150 works listed by his publisher, and more than 100 still unpublished (many of them housed in the Music Division of the Library of Congress), Barber is regarded as one of America’s foremost composers.

Barber was born on March 9, 1910 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, about 25 miles from Philadelphia. His father, Roy, was a prominent physician and the president of the West Chester School Board. Barber’s mother, Marguerite McLeod Beatty (called Daisy), was the sister of Louise Homer, a celebrated contralto with the Metropolitan Opera and wife of composer Sidney Homer. Thus Barber was gifted with a financially secure background, which gave him the opportunity to study with the best musicians, and with a mentor in his Uncle Sidney, who monitored and encouraged the young man’s musical career for over three decades.

When he was six years old, Barber began improvising melodies at the piano, and by the time he was seven he was composing music. In 1919 he began studying piano with William Hatton Green, once a pupil of Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna. At age twelve, he accepted a position as organist at the First Presbyterian Church; this employment was short lived, however, due to the young Barber’s refusal to hold fermatas in hymns and responses. Soon after entering high school, around age fourteen, Barber commuted every Friday to Philadelphia to study music at the newly founded Curtis Institute of Music.

During his nine years of study at Curtis, Barber took on a trifecta of musical disciplines and distinguished himself in all three. He studied piano with George Boyle and Isabelle Vengerova, voice with Emilio de Gogorza, and composition with Rosario Scalero. It was also at Curtis, in the fall of 1928, that Barber met fellow composer Gian Carlo Menotti. Barber and Menotti would share a close personal and professional relationship that lasted over fifty years, until Barber’s death. The compositions Barber penned during his Curtis years include Serenade for String Quartet (1928); Three Songs, op. 2 (1928-34); and Dover Beach (1931), a chamber work for voice and string quartet that Barber, an accomplished baritone, recorded in 1935.

It was during his Curtis years that Barber made several trips to Europe, including to Cadegliano, Italy, Menotti’s home town. These European excursions would have a deep impact on Barber’s compositional style and on his intellectual development. Upon graduation from Curtis in 1934, Barber gained an important and loyal patron: Mary Curtis Bok, founder of the Curtis Institute. Mrs. Bok not only provided financial assistance to Barber (in fact, she helped Barber and Menotti purchase Capricorn, their home in Mount Kisco, New York, in 1943), she also actively promoted his career.

In 1938, Barber earned international recognition when the legendary Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini conducted the NBC Symphony Orchestra in a broadcast of two of Barber’s works: First Essay and the Adagio for Strings (an arrangement of the second movement of the composer’s String Quartet in B minor). The result of this recognition was manifested in the many commissions offered to Barber from highly respected performers and ensembles, including the U.S. Army Air Forces–in which Barber served from 1942 to 1945–which commissioned the Second Symphony (1943); Raya Garbousova, who commissioned the Cello Concerto (1945); and soprano Eleanor Steber, who commissioned the orchestral song Knoxville, Summer of 1915 (1947). At the peak of his career, Barber was awarded two Pulitzer Prizes. The first was in 1958 for the opera Vanessa, which had a libretto by Menotti and was staged by the Metropolitan Opera, featuring Eleanor Steber in the title role. The second Pulitzer was given in 1963, for the Piano Concerto, which was written for the inaugural week of Philharmonic Hall at Lincoln Center and premiered there by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, with Erich Leinsdorf conducting and John Browning as the soloist. In 1966, Barber was commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera to write an opera for the grand opening of their new opera house at Lincoln Center. He worked on Antony and Cleopatra, his second full-length opera, with librettist-producer Franco Zeffirelli. Ironically, this honored commission, intended as a tribute to Barber’s work, resulted in the composer’s greatest failure. The opening night was widely seen as nothing less than a fiasco, due to Zeffirelli’s extravagant overproduction as well as the technical and mechanical difficulties experienced by the new opera house.

From 1966 on, Barber’s compositional output decreased significantly. He was plagued with bouts of depression and alcoholism, as well as creative blocks that severely hampered his productivity. During the last year of his life, he was frequently hospitalized for treatment of cancer. He died on January 23, 1981, and was buried next to his mother in the Barber family plot at the Oaklands Cemetery in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

Barber’s hallmark among American composers lies in the fact that he embraced a lyrical and expressive compositional style and shunned nearly all of the experimental trends that penetrated music in the first half of the 20th century. Unlike many of his contemporaries, who dabbled with folk music, twelve-tone music, or serial music, Barber adhered to traditional European 19th-century models for most of his works. This was undoubtedly as a result of his studies with Scalero at the Curtis Institute, plus the advice and guidance of his Uncle Sidney.

Although Barber composed at least one work for every major genre, he possessed a natural affinity for songs, and could write them with ease, often generating songs as a diversion from a larger composition with which he was struggling. It is in the song medium that Barber’s lyrical gift is most aptly displayed and his legacy celebrated.

–Stephanie Poxon, Ph.D.

Related Information

Songs

A Last Song (op. 41, no. 1)

Samuel Barber

Robert Graves

At Saint Patrick's Purgatory

Samuel Barber

Anonymous

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

Bessie Bobtail (op. 2, no. 3)

Samuel Barber

James Stephens

Song Collection: Three Songs, Op. 2

Church Bell at Night

Samuel Barber

Anonymous

Howard Mumford Jones

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

Despite and Still, Op. 41

Song CollectionSamuel Barber

Robert Graves

Theodore Roethke

James Joyce

Despite and Still (op. 41, no. 5)

Samuel Barber

Robert Graves

Song Collection: Despite and Still, Op. 41

Hermit Songs, Op. 29

Song CollectionSamuel Barber

Anonymous

I Hear an Army (op. 10, no. 3)

Samuel Barber

James Joyce

Song Collection: Three Songs, Op. 10

In the Dark Pinewood

Samuel Barber

James Joyce

In The Wilderness (op. 41, no. 3)

Samuel Barber

Robert Graves

Song Collection: Despite and Still, Op. 41

Knoxville: Summer of 1915 (op. 24)

Samuel Barber

James Agee

My Lizard (Wish For a Young Love) (op. 41, no. 2)

Samuel Barber

Theodore Roethke

Song Collection: Despite and Still, Op. 41

Monks and Raisins (op. 18, no. 2)

Samuel Barber

José García Villa

Song Collection: Two Songs, Op. 18

Nocturne (op. 13, no. 4)

Samuel Barber

Frederic Prokosch

Nuvoletta (op. 25)

Samuel Barber

James Joyce

Promiscuity

Samuel Barber

Anonymous

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

Rain Has Fallen (op. 10, no. 1)

Samuel Barber

James Joyce

Song Collection: Three Songs, Op. 10

Sea-Snatch

Samuel Barber

Anonymous

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

Serenader

Samuel Barber

George H. Dillon

Sleep Now (op. 10, no. 2)

Samuel Barber

James Joyce

Song Collection: Three Songs, Op. 10

Solitary Hotel (op. 41, no. 4)

Samuel Barber

James Joyce

Song Collection: Despite and Still, Op. 41

St. Ita's Vision

Samuel Barber

Anonymous

Chester Kallman

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

Sure on This Shining Night (op. 13, no. 3)

Samuel Barber

James Agee

The Crucifixion

Samuel Barber

Anonymous

Howard Mumford Jones

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

The Daisies (op. 2, no. 1)

Samuel Barber

James Stephens

Song Collection: Three Songs, Op. 2

The Desire for Hermitage

Samuel Barber

Anonymous

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

The Heavenly Banquet

Samuel Barber

Anonymous

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

The Monk and His Cat (op. 29, no. 8)

Samuel Barber

W. H. Auden

Anonymous

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

The Praises of God

Samuel Barber

Anonymous

W. H. Auden

Song Collection: Hermit Songs, Op. 29

The Queen's Face on the Summery Coin (op. 18, no. 1)

Samuel Barber

Robert Horan

Song Collection: Two Songs, Op. 18

Three Songs, Op. 10

Song CollectionSamuel Barber

James Joyce

Three Songs, Op. 2

Song CollectionSamuel Barber

James Stephens

A. E. Housman

Two Songs, Op. 18

Song CollectionSamuel Barber

Robert Horan

José García Villa

With Rue My Heart is Laden (op. 2, no. 2)

Samuel Barber

A. E. Housman

Song Collection: Three Songs, Op. 2

Videos

Recordings

An American Song Album

(Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland and Jake Heggie)

2019

Lineage

(Samuel Barber, Elliott Carter and Charles Ives)

2017

stopping by

(Mark Abel, Samuel Barber, Amy Marcy Beach, Leonard Bernstein, Charles Wakefield Cadman, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, Celius Dougherty, John Woods Duke, Stephen Foster, Charles Griffes and Ned Rorem)

2013

Something to Sing About

(Samuel Barber, William Bolcom, Aaron Copland, John Corigliano, John Harbison, Charles Ives and Ned Rorem)

2011

My Name is Barbara

(Samuel Barber, Charles Griffes, Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein)

2005

Americans in Paris

(Samuel Barber, Leonard Bernstein, Louis Campbell-Tipton, Henry Hadley, Charles Martin Loeffler, Charles Ives and Kurt Weill)

2000

Modern American Vocal Works

(Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson)

1954

I Want Magic!

(Samuel Barber, Leonard Bernstein and André Previn)

1998

American Anthem: From Ragtime to Art Song

(Samuel Barber, Lee Hoiby, Charles Ives, John Musto, John Jacob Niles, Ned Rorem, Aaron Copland and William Bolcom)

1998

American Songs (Barbara Bonney)

(Dominick Argento, Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland and André Previn)

1998

I Will Breathe a Mountain

(Samuel Barber, Leonard Bernstein and William Bolcom)

1997

American Songs (Jennifer Larmore)

(Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland, John Woods Duke, Jake Heggie, Lee Hoiby, Charles Ives, Charles Naginski and John Jacob Niles)

1997

Sure on This Shining Night

(Samuel Barber, George Whitefield Chadwick, Charles Ives, John Corigliano, Aaron Copland, William Bolcom, Ned Rorem, Richard Hageman, Charles Griffes, Victor Herbert, Horatio Parker, John Musto, Amy Marcy Beach, Theodore Chanler and Virgil Thomson)

1997

But Yesterday is Not Today: The American Art Song, 1927-1972 (1977)

(Samuel Barber, Paul Bowles, Theodore Chanler, Aaron Copland, John Woods Duke, Robert Helps and Roger Sessions)

1977

View recording

Paul Sperry Sings an American Sampler

(Samuel Barber, Robert Beaser, William Bolcom, William Billings, Elliott Carter, Celius Dougherty, John Woods Duke, Stephen Foster, Charles Griffes, John Musto, Ned Rorem, May Swenson, Louise Talma, Hugo Weisgall and Kurt Weill)

1995

Barber: The Complete Songs

(Samuel Barber)

1994

Barbara Hendricks Sings Bach, Barber & Copland

(Samuel Barber and Aaron Copland)

1994

Where the Music Comes From

(Lee Hoiby, Celius Dougherty, Ned Rorem, Henry T. Burleigh, Samuel Barber, Arthur Farwell and Charles Griffes)

1991

Beloved That Pilgrimage

(Aaron Copland, Theodore Chanler and Samuel Barber)

1991

Songs by 20th Century American Composers (Vol. I & II)

(Ernst Bacon, Samuel Barber, Paul Bowles, John Alden Carpenter, Theodore Chanler, Aaron Copland, Charles Griffes, Charles Ives, Otto Luening, Edward MacDowell, Virgil Thomson and Ned Rorem)

1962

Eleanor Steber in Concert

(Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland and Katherine Kennicott Davis)

1958

Kirsten Flagstad, Vol. 4

(Samuel Barber, James H. Rogers, John Alden Carpenter, Richard Hageman and Stephen Foster)

1936

Books

Samuel Barber: The Composer & His Music

Samuel Barber

Modern Music-Makers: Contemporary American Composers

Originally published in 1952, this volume is dated but does contain a thorough biography, chronology, and catalog for many important song composers, including Charles Ives, John Alden Carpenter, Marion Bauer, William Grant Still, Virgil Thomson, Aaron Copland, Lousie Talma, Samuel Barber, William Schuman, and Leonard Bernstein.

Sheet Music

28 Songs by American and British Composers

Composer(s): John Duke

Song(s): Barber: Must the Winter Come so Soon?

Bernstein: Two Love Songs (Extinguish My Eyes, When My Soul Touches Yours)

Bowles: Heavenly Grass

Carpenter: When I Bring to You Colour'd Toys

Corigliano: Christmas at the Cloisters, The Unicorn

Dougherty: Sound the Flute!

Duke: Peggy Mitchell

Hoiby: An Immorality

Moore: The Dove Song (The Wings of the Dove)

Sargent: Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

Thomson: English Usage, The Tiger

Vaughan Williams: Hugh's Song of the Road

Wells: Everyone Sang

Samuel Barber Sheet Music

Buy via Music Sales ClassicalMusic for Soprano and Orchestra (Piano/Vocal)

Composer(s): Samuel Barber

Voice Type: Soprano

Buy via Music Sales ClassicalSamuel Barber: 65 Songs (G. Schirmer, high voice)

Composer(s): Samuel Barber

Voice Type: High

Buy via Hal LeonardSamuel Barber: 65 Songs (G. Schirmer, medium-low voice)

Composer(s): Samuel Barber

Voice Type: Medium/Low

Buy via Music Sales ClassicalSamuel Barber: Collected Songs

Composer(s): Samuel Barber

Song(s): 1. A Last Song (op. 41, no. 1)

2. My Lizard (Wish For a Young Love) (op. 41, no. 2)

3. In The Wilderness (op. 41, no. 3)

4. Solitary Hotel (op. 41, no. 4)

5. Despite and Still (op. 41, no. 5)

Songs by 22 Americans

Composer(s): Samuel Barber

Leonard Bernstein

Paul Bowles

John Alden Carpenter

Celius Dougherty

John Duke

Charles Tomlinson Griffes

Richard Hageman

Charles Naginski

William Roy

Gladys Rich

Virgil Thomson

Elinor Remick Warren

Voice Type: High

Buy via Sheet Music PlusThe First Book of Soprano Solos

Composer(s): Louis Campbell-Tipton, Samuel Barber, Edward MacDowell, Oley Speaks

Buy via Sheet Music Plus