Listen

Track:

About

It is perhaps ironic that a composer of Russian-Jewish immigrant extraction would be more closely identified with Americanist music than any of his Yankee colleagues. Yet, in many ways, Aaron Copland, and his contemporary Leonard Bernstein, exerted such profoundly shaping influences on American music that they became institutions in their own right. Composer, conductor, writer and lecturer, teacher, advocate of modern music, a founder of the American Composers Alliance and the Tanglewood Festival, Copland commanded a central role in this country’s musical life for almost seventy years.

Born in Brooklyn on November 14, 1900, Copland’s early musical inclinations surfaced in his childhood fondness for making up songs. At 12 he began piano lessons and at 17 played his first public performance, at Wanamaker’s Department Store in Manhattan. Fixing his sights on a musical career, Copland undertook harmony studies with Rubin Goldmark and advanced piano lessons with Victor Wittgenstein and Clarence Adler, all musicians in the conservative European mold.

1921 proved to be a watershed year for Copland. He encountered what his teachers called radical modern music–Ives and Ravel; he won a scholarship to a newly formed school for American musicians at Fontainebleau; and he set sail for Paris in June of that year. For the next three years he would study with Nadia Boulanger, compose his first serious works, and associate with a stimulating circle of American expatriates and French intellectuals, among them his cousin and later the distinguished theatre critic Harold Clurman, the cubist painter Marcel Duchamp, the conductor Serge Koussevitsky, and composer Roger Sessions.

Upon returning to America in 1924, Copland received the first public performances of his compositions, his Organ Symphony in 1924 with Walter Damrosch conducting, Music for Theatre in 1925, and his Piano Concerto in 1926. After another brief sojourn in Paris in 1926-27, Copland settled in New York to engage in a number of ventures that would have significant effects in creating a public for contemporary American music. He began his pedagogical career in 1927, as a lecturer at New York’s School for Social Research, creating the material for his 1938 book What to Listen for in Music. In 1928, with Sessions, he launched an influential concert series that showcased experimental contemporary composers such as Theodore Chanler, Walter Piston, Carlos Chàvez, Virgil Thomson, Marc Bltizstein, Roy Harris, Paul Bowles, Darius Milhaud, as well as his own and Sessions’s work. That same year he joined the League of Composers and founded the Cos Cob Press, dedicated to publishing new American music.

The decade of the 1930’s and the Great Depression created a climate of social awareness and political ferment, in which Copland, with his progressive-leftist political philosophy, would search for ways to make music more accessible to the masses. The composer’s major works from this period include his opera The Second Hurricane (created for children and performed at the Henry Street Settlement), and his popular ballet Billy the Kid, the first work in which Copland began to use American folk elements in his music. The era’s focus on labor issues also had its effects on the music business, where Copland became active in a number of institutions designed to further musicians’ professional lives: ASCAP, Arrow Music Press, the American Composers Orchestra, and the American Music Center. But perhaps the most significant institutional involvement for Copland began in 1940: his association with the Berkshire Music Center and the Tanglewood Festival, where he would teach and work for several decades to come.

A spate of enduring compositions followed in the 1940’s, among them A Lincoln Portrait (1942), into which Copland incorporated American folk tunes, his ballet Rodeo (1943), his Fanfare for the Common Man (1943), and his modern dance work for Martha Graham, Appalachian Spring (1944). It was the last of these, with its haunting Shaker tune “Simple Gifts,” that won for Copland the Pulitzer Prize and catapulted him into national prominence. The composer inaugurated the new decade by completing his song cycle Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson (1950), eight of which he later orchestrated. While composing the Dickinson cycle, Copland worked on his two sets of Old American Songs, arrangements that became so popular in their piano and orchestral versions as to eclipse the original folk tunes on which they were based. To this period of vocal writing also belongs Copland’s second opera, The Tender Land, to a Steinbeckesque libretto by Erik Johns about a Midwestern family during the Depression. Premiered by the New York City Opera in 1954 and revised for Tanglewood in 1955, the work failed to win critical approval.

The 1950’s were also marred for Copland by the McCarthy hearings. A controversy over programming A Lincoln Portrait at Eisenhower’s 1953 inauguration led to Copland’s being summoned to testify in a secret session. Refusing to implicate any of his colleagues and skillfully fielding questions about his own socialist politics, Copland managed to survive the ordeal without betraying any of his friends or principles. In the remaining 20 years that Copland would compose, he briefly flirted with serialism before returning to a tonal style. After 1973 he devoted himself increasingly to conducting. In his final decade, as awards and tributes poured in, Copland’s mental powers began to fail him. He withdrew to his home in Peekskill, New York to mourn the passing of colleagues and friends, among them his companion, Victor Kraft, who had died in 1976. Copland died on December 2, 1990.

–Thomas Hampson and Carla Maria Verdino-Süllwold, PBS I Hear America Singing

Most people know that Aaron Copland was a composer and that his compositions include Appalachian Spring, Fanfare for the Common Man, and the “Hoedown” from Rodeo. What people may not realize is that Copland’s influence on American music extended far beyond the realm of composition–he was also a teacher, lecturer, author, editor, and conductor. Because of his involvement in these different facets of artistic expression, and because he created a distinctly American style of composition, he is frequently referred to as the “Dean of American Music.”

Aaron Copland was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 14th, 1900, the youngest of five children. His parents, Harris Morris Copland and Sarah Mittenthal Copland, were Jewish immigrants from Russia. They arrived in Brooklyn in 1877, and adopted an Anglicized version of their original surname, Kaplan. Aaron’s earliest musical training came in the form of piano lessons from his sister Laurine. His formal training began in 1914, with piano lessons from Leopold Wolfsohn; at age sixteen he began studying counterpoint and composition with Rubin Goldmark. He was discouraged, however, by Goldmark’s strict adherence to the conservative masters of the 19th century, and took it upon himself to explore the music of the more innovative and modern composers of his day, including Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, and Alexander Scriabin. After four years under Goldmark’s tutelage, Copland decided to follow in the footsteps of many of his contemporaries and head to Europe to further his musical training.

He moved to France in June of 1921 and attended the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau. It was during his study at Fontainebleau that Copland became acquainted with the legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. Upon completion of the summer courses, he followed Boulanger to Paris for composition lessons at her home on Rue Ballu. Among the other young American composers in Boulanger’s studio were Herbert Elwell, Melville Smith, and Virgil Thomson. Copland studied with Boulanger until 1924, and she was one of the most important influences on his compositional career. She encouraged him to expand his horizons by studying all periods of classical music. It was through Boulanger that Copland’s first composition was published: The Cat and the Mouse, a work for piano solo. This “scherzo humoristique,” which Copland completed in March 1920, was published by Durand and Sons in 1921.

Upon his return to the United States in 1924, Copland was preoccupied with a work he was writing on commission for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Through her associations with Walter Damrosch, then conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra, and Serge Koussevitzky, the recently appointed conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Boulanger had secured the commission for Copland, as well as two performances. The result was Symphony for Organ and Orchestra, which was first heard on January 11th, 1925, with the New York Symphony Orchestra under Damrosch’s baton and with Boulanger as soloist. The premiere was a success and essentially launched Copland’s career as a promising young American composer. It was also during this time in New York that Copland became involved with the League of Composers, and with the organization’s journal, Modern Music, which started publishing articles by Copland in 1925. In addition, along with his colleague Roger Sessions, Copland organized the Copland-Sessions Concerts of Contemporary Music, which took place from 1928 to 1932, mostly in New York. The objective was to expose audiences to European avant-garde works that had not previously been heard in the United States.

During the Great Depression, Copland sought to produce works that appealed to mass audiences, works that spoke to a wide variety of individuals during difficult economic times. His move in this direction may have been inspired by the composition of El Salón México (1936), which he described as a model of “imposed simplicity.” The piece was influenced by a trip to Mexico in 1932. By infusing elements of Mexican folk music into the writing, Copland was able to communicate to a larger public. This conscious use of folk materials to produce music in a melodic and accessible medium foreshadowed Copland’s success with ballets such as Billy the Kid (1938), Rodeo (1942), and the Pulitzer Prize-winning Appalachian Spring (1944). This last piece is known especially for its masterful set of variations on the Shaker tune “Simple Gifts.” Copland also generated music of a patriotic nature during this time, with works such as A Lincoln Portrait (1942) for orchestra and narrator, and Fanfare for the Common Man (1942) for brass and percussion, both of which were intended to boost American morale. These works remain synonymous with American patriotism.

During the 1950’s, Copland focused his attention on writing for the voice. He produced the majority of his vocal works during this decade (a notable exception is his children’s opera, The Second Hurricane, written in 1936). The first major vocal work was completed in 1950: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson, considered among the great song cycles of the 20th century. Copland also fashioned two sets of song collections based on American folk tunes, which he dubbed Old American Songs; the first set appeared in 1950, and the second set followed two years later. During this decade, Copland produced his only full-length opera: a commission by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein to create music for The Tender Land (1954), an opera based on James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Although the work has not entered the mainstream repertoire of the operatic stage, it has met with some success, and one of its most memorable arias is often performed as “Laurie’s Song,” for soprano and piano.

Toward the end of his life, from about 1960 on, Copland found himself more occupied as conductor than composer. In his later years he had great difficulty capturing his inspiration through composing; in his own words, “It was exactly as if someone had simply turned off a faucet.” He spent his time revising his earlier compositions and preserving his extant works, through a series of recordings in the 1970s for Columbia Records. Despite his energy and commitment to these projects, Copland suffered from the beginning stages of Alzheimer’s disease and was frustrated by his inability to harness his memory. By the 1980s, his mind had deteriorated. He succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease and respiratory failure on December 2nd, 1990, a few days after his ninetieth birthday.

Further information, including holograph manuscripts, sketches, letters, and other primary resources are available through the Library of Congress’ Online Aaron Copland Collection.

–Stephanie Poxon, Ph.D.

Related Information

Songs

At the River

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 2

Ching-a-Ring Chaw

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 2

Dear March, Come In!

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

Going to Heaven!

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

Heart, We Will Forget Him

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

I Bought Me a Cat

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 1

I Felt a Funeral in My Brain

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

I've Heard an Organ Talk Sometimes

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

Long Time Ago

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 1

Nature, the Gentlest Mother

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

Old American Songs, Set 1

Song CollectionAaron Copland

Old American Songs, Set 2

Song CollectionAaron Copland

Poet's Song

Aaron Copland

E. E. Cummings

Simple Gifts

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 1

Sleep is Supposed to Be

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

The Boatmen's Dance

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 1

The Chariot

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

The Dodger

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 1

The Golden Willow Tree

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 2

The Little Horses

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 2

The World Feels Dusty

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

There Came a Wind Like a Bugle

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

Song CollectionAaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

When They Come Back

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

Why Do They Shut Me Out of Heaven?

Aaron Copland

Emily Dickinson

Song Collection: Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

Zion's Walls

Aaron Copland

Song Collection: Old American Songs, Set 2

Videos

Recordings

An American Song Album

(Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland and Jake Heggie)

2019

A Certain Slant of Light

(Aaron Copland, Jake Heggie and Michael Tilson Thomas)

2018

stopping by

(Mark Abel, Samuel Barber, Amy Marcy Beach, Leonard Bernstein, Charles Wakefield Cadman, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, Celius Dougherty, John Woods Duke, Stephen Foster, Charles Griffes and Ned Rorem)

2013

Something to Sing About

(Samuel Barber, William Bolcom, Aaron Copland, John Corigliano, John Harbison, Charles Ives and Ned Rorem)

2011

Between the Bliss and Me. . . Songs to Poems of Emily Dickinson

(Ernst Bacon, Aaron Copland, John Woods Duke, Arthur Farwell, Lee Hoiby, Lori Laitman and Richard Pearson Thomas)

2009

Abraham Lincoln Portraits

(Ernst Bacon, Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, Charles Ives and George Frederick McKay)

2008

Marilyn Horne: Complete Decca Record

(George M. Cohan, Aaron Copland and Stephen Foster)

2008

American Classics: Foster, Griffes, Copland

(Stephen Foster, Charles Griffes and Aaron Copland)

2008

Songs of America: Oral Moses

(Uzee Brown, Jr., Henry T. Burleigh, Aaron Copland, Florence Price and Howard Swanson)

2007

The Deepest Desire

(Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland and Jake Heggie)

2006

Dwell in Possibility: Dickinson in Song

(Ernst Bacon, Aaron Copland, Celius Dougherty, John Woods Duke, Lee Hoiby, Richard Hundley, Jake Heggie, Lori Laitman, Libby Larsen, Etta Parker, Simon Sargon, Leo Smit and Richard Pearson Thomas)

2004

American Anthem: Songs and Hymns

(Aaron Copland, John Rosamond Johnson and Randall Thompson)

2001

Voices From Elysium: Copland, Crawford

(Aaron Copland, Ruth Crawford Seeger, Miriam Gideon and Louise Talma)

1998

American Anthem: From Ragtime to Art Song

(Samuel Barber, Lee Hoiby, Charles Ives, John Musto, John Jacob Niles, Ned Rorem, Aaron Copland and William Bolcom)

1998

American Songs (Barbara Bonney)

(Dominick Argento, Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland and André Previn)

1998

American Songs (Jennifer Larmore)

(Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland, John Woods Duke, Jake Heggie, Lee Hoiby, Charles Ives, Charles Naginski and John Jacob Niles)

1997

American Songbook - The American Music Collection, Vol. 3

(Amy Marcy Beach, Leonard Bernstein, Marc Blitzstein, William Bolcom, Aaron Copland, Charles Ives, Betty Jackson King, Libby Larsen and Kurt Weill)

1996

Barbara Hendricks Sings Bach, Barber & Copland

(Samuel Barber and Aaron Copland)

1994

Songs of America

(William Bolcom, Charles Wakefield Cadman, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, Ruth Crawford Seeger, Stephen Foster, Charles Ives, Carrie Jacobs-Bond, Sergius Kagen, Theodore Roethke, Ned Rorem, Carl Sandburg, William Jay Smith and Gertrude Stein)

1988

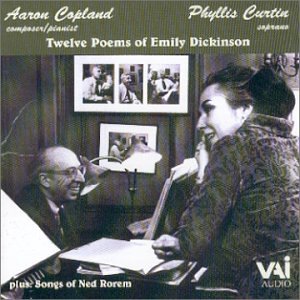

American Songs: Copland, Rorem, Sessions

(Aaron Copland, Ned Rorem and Roger Sessions)

1971

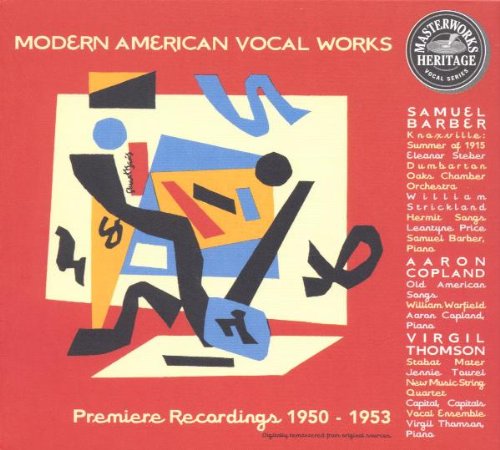

Modern American Vocal Works

(Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson)

1954

Books

Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man

Copland: 1900-1942

Copland: Since 1943

The Selected Correspondence of Aaron Copland

Modern Music-Makers: Contemporary American Composers

Originally published in 1952, this volume is dated but does contain a thorough biography, chronology, and catalog for many important song composers, including Charles Ives, John Alden Carpenter, Marion Bauer, William Grant Still, Virgil Thomson, Aaron Copland, Lousie Talma, Samuel Barber, William Schuman, and Leonard Bernstein.

The Music Makers

Includes first person chapters by American composers Aaron Copland, Milton Babbitt, Miriam Gideon, and Earle Brown, as well as American scholars and teachers, conductors, and performers.

Sheet Music

15 Art Songs by American Composers (High Voice)

Composer(s): Dominick Argento, Leonard Bernstein, Theodore Chanler, Aaron Copland, John Duke, Richard Hundley, Ned Rorem

Voice Type: High

Buy via Sheet Music Plus15 Art Songs by American Composers (Low Voice)

Composer(s): Dominick Argento, Leonard Bernstein, Theodore Chanler, Aaron Copland, John Duke, Richard Hundley, Ned Rorem

Voice Type: Low

Buy via Sheet Music PlusAaron Copland Sheet Music

Buy via Boosey & HawkesTwelve Poems of Emily Dickinson

Composer(s): Aaron Copland

Song(s): 1. Nature, the Gentlest Mother

2. There Came a Wind Like a Bugle

3. Why Do They Shut Me Out of Heaven?

4. The World Feels Dusty

5. Heart, We Will Forget Him

6. Dear March, Come In!

7. Sleep is Supposed to Be

8. When They Come Back

9. I Felt a Funeral in My Brain

10. I've Heard an Organ Talk Sometimes

11. Going to Heaven!

12. The Chariot