Essay

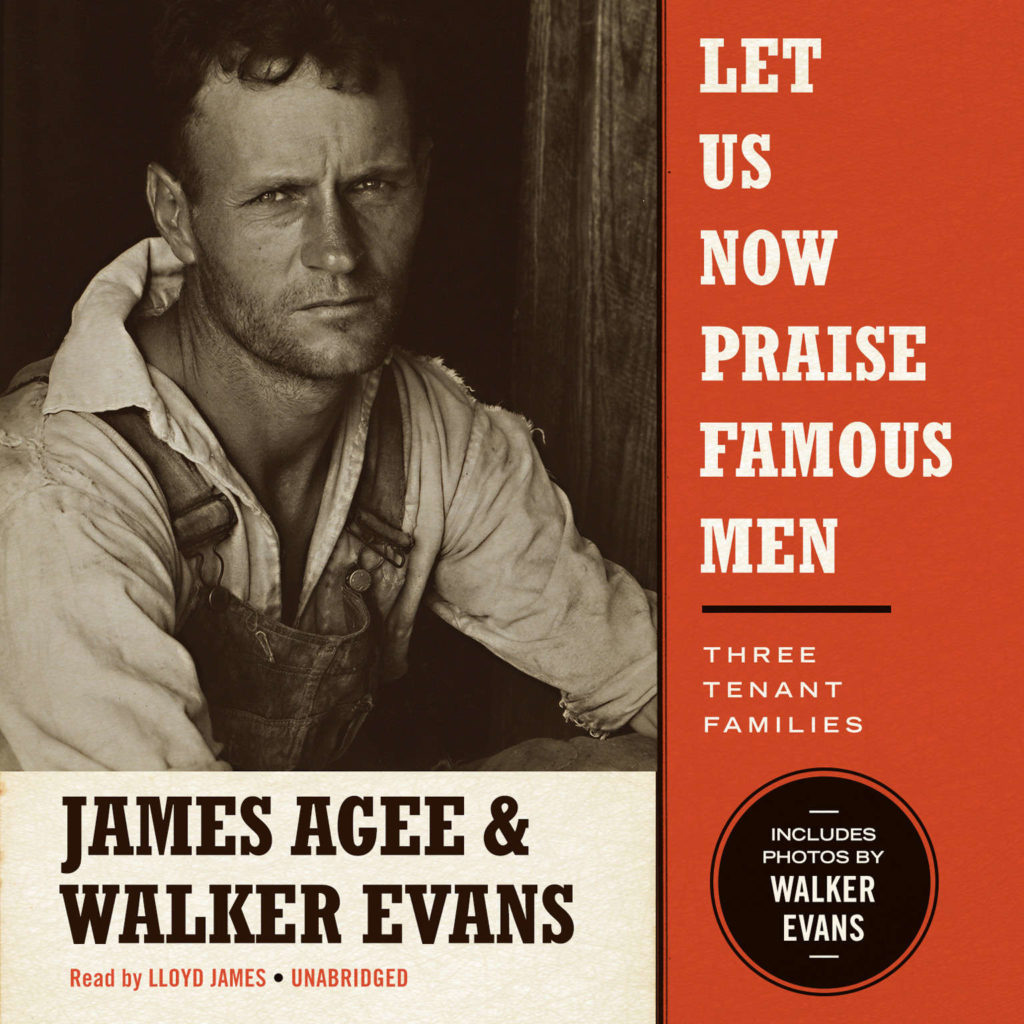

Photo: “Frank Tengle, Cotton Sharecropper. Hale County, Alabama” by Walker Evans (1935 or 1936), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Digital ID fsa 8c52262

The Great Depression ushered America into an era of social consciousness and liberal reform. In the decade of the 1930’s, under Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, writers, artists, photographers, musicians, and performers were marshaled to create works that documented American life, sponsored by government programs such as the F.S.A. (Farm Security Administration) and the W.P.A. (Work Projects Administration). The Great Depression had been a rude awakening from the escapism of the Roaring Twenties, so it was not surprising that realism would become the preferred modus operandi for creative artists. And what more realistic genre than the photograph!

The 1930’s and 1940’s saw a golden age in photojournalism in America in which photographers such as Ben Shahn, Arthur Rothstein, Dorothea Lange, and Margaret Bourke-White created visual corollaries to the writings of Erskine Caldwell (Tobacco Road), John Steinbeck (The Grapes of Wrath), and Archibald MacLeish (Land of the Free). Another highly respected photographer who had already been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York before he joined the F.S.A. was Walker Evans, whose master images have been preserved in two published volumes.

The first of these appeared as American Photographs in 1938. In the collection, selected from the larger body of photographs he produced for the F.S.A. report, Evans chronicles a society in the making. With his images of simple folk immersed in the rituals of American society and surrounded by a carefully composed clutter of objects, Evans’s lens often operates with an unsparing irony as he presents not only the ideals to which America aspired but also the dichotomies between reality and those ideals.

The second project, a stirring literary-photography collaboration, began in 1936 when Evans, eager for a more ambitious challenge, accepted the offer from Fortune Magazine to accompany their reporter, his friend James Agee, to the Deep South. There they traveled the countryside and boarded for some time with three Appalachian families. The resulting reportage was a poetic, passionately argued verbal and visual study of hope and hopeless in a troubled democracy. Fortune declined to publish it, and it would take five years for it to appear, with an expanded text, in 1941 as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

–Thomas Hampson and Carla Maria Verdino-Süllwold, PBS I Hear America Singing