Audio

Track:

About

Sidney Homer, who created over 100 songs, earned royalties of $13,577.14 in a five month period in 1914-1915–a considerable sum which indicates the pervasiveness and popularity of his music at the height of his fame. A list advertised by G. Schirmer cites Marcella Sembrich, Johanna Gadski, Lillian Nordica, Louise Homer, Alma Gluck, Christine Miller, Mme. Van Niessen-Stone, David Bispham, Herbert Witherspoon, Francis Rogers, Emilio de Gorzoga, Heinrich Meyn, George Hamlin, Cecil Fanning, Charles Clark, Carl Dufft, Charles Washburn, and Evan Williams as artists who regularly programmed Homer’s songs from the 50 works that firm published.

And yet in the years following Sidney Homer’s death, despite the efforts of his nephew, Samuel Barber, to issue compilations of his best work; the tireless attempts of his daughter, Kathryn Homer Fryer, to urge Schirmer to reprint works long out-of-print; and the championing of a few committed recitalists, Homer’s songs fell into neglect.

Sidney Homer’s song catalogue is diverse. Because he wrote with his wife’s contralto in mind, his vocal line tends to be expansive and often bold. His taste in texts was eclectic, encompassing the Anglo-Celtic Romantics (Blake, Browning, Yeats), the American jazz poets (Vachel Lindsay), nursery rhymes and children’s verse (Mother Goose), and humorous folk narratives (Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s “Casey at the Bat”). The musical genres in which he worked ranged from big Romantic old songs like “Dearest” to Loewe-like ballads such as “The Song of the Shirt,” with its socialist overtones; from delicate creations like “A Sick Rose” to tunes like “A Banjo Song” or “Mammy’s Lullaby,” which were imitative of the old slave songs. The range of emotions Homer was able to evoke stretched from the impassioned and dramatic (“Michael Robartes Bids his Beloved Be at Peace”) to the child-like (“Sing-Song”) to the ironic (“The King of the Fairy Men”), or to the melancholy tenderness of “When Death to Either Shall Come.” These emotions are colorfully indicated by the dynamic and phrasing marks that Homer placed on his manuscripts: “allegretto with pessimism;” “molto lento with deep emotion;” “sostenuto, calmly with religious feeling;” “allegro energico, with fine irony;” “allegro, quaintly and with refinement;” “allegro molto with exulting freedom;” “adagio, with passion.”

Perhaps Homer’s greatest gift as a songwriter was his ability to let the story tell itself through the music. His “General William Booth Enters Into Heaven” is an admirable case in point, especially if one compares it to Charles Ives’s idiosyncratic setting of the same text. Homer’s setting incorporates the traditional Salvation Army tune “Are You Washed in the Blood of the Lamb?” into the refrain of the song, juxtaposing this with the thrusting rhythms of Vachel Lindsay’s text, thereby creating the dramatic effect of propulsion and reflection, as the song builds to its poignant closing encounter between Booth and Jesus.

Homer was born in Boston on December 9, 1864, the youngest child of deaf parents. The Homer family was left an annuity by a wealthy uncle, which insured their comfort and permitted 16- year-old Sidney to travel to London to pursue his literary inclinations. It was there that a Mr. Green, music critic of the London Daily News, discovered the youth’s musical talent and encouraged him to study further, first in Leipzig, then in Boston with Chadwick, and finally with Rheinberger in Munich.

Returning to Boston in 1888, Homer opened his own music studio, where one of his first pupils was the Philadelphia contralto Louise Beatty. They married two years later and departed for Paris, where Louise completed her vocal studies and Sidney began to compose in earnest. Upon their return to New York, Louise Homer became ensconced as one of the brightest stars of the Metropolitan Opera’s Golden Age, while Sidney’s songs, now published by G. Schirmer, became repertory staples.

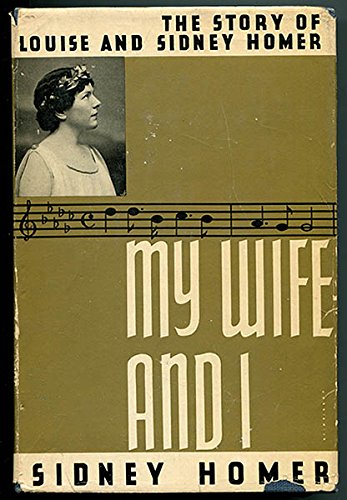

A devoted couple, they raised six children, two of whom pursued musical careers: Louise Stires became a soprano, and Kathryn Fryer a pianist, who sometimes accompanied her mother’s recitals. Sidney published a memoir of their marriage, My Wife and I, in 1939. After Louise Homer’s retirement from the stage in 1939, the couple moved to Winter Park, Florida, where Sidney Homer died seven years after Louise, in 1953.

–Thomas Hampson and Carla Maria Verdino-Süllwold, PBS I Hear America Singing

Related Information

Songs

Videos

Recordings

Wondrous Free

(Leonard Bernstein, Paul Bowles, John Alden Carpenter, John Woods Duke, Stephen Foster, Sidney Homer, Francis Hopkinson, Charles Ives, Edward MacDowell, William Grant Still and Elinor Remick Warren)

2009

View recording

Paul Robeson - The Complete EMI Sessions

(Charles Wakefield Cadman, Henry T. Burleigh, Benjamin Carr, Will Marion Cook, Stephen Foster, Langston Hughes, Carrie Jacobs-Bond, Ethelbert Nevin, Oscar Rasbach and Oley Speaks)

1938

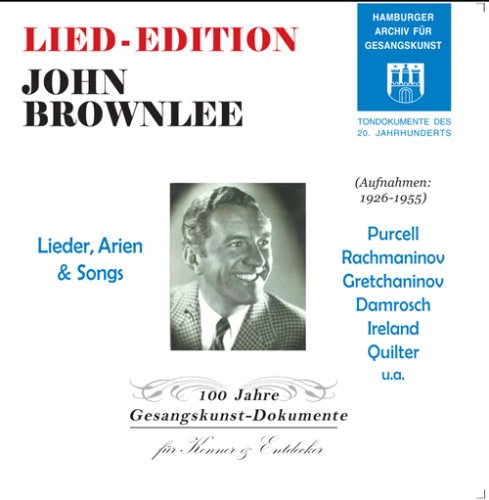

John Brownlee: Lied-Edition

(Louis Campbell-Tipton, Walter Damrosch and Sidney Homer)

2007